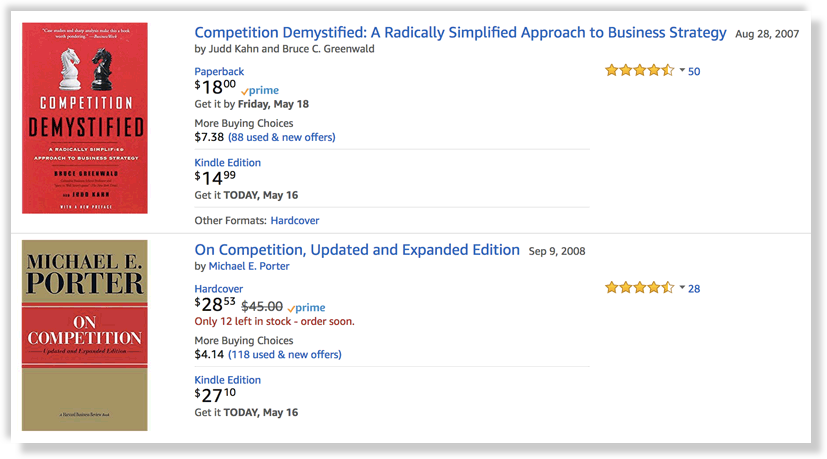

an Amazon query for books about competition yields 2(!) relevant results:

these books, written 10 years ago, advise traditional enterprises on global expansion and positioning.

what about tech companies?

agenda

in this essay i’ll distill a few ideas on how, why, and when to compete as a tech company, with other tech companies.

we’ll discuss specific examples, using household names, to debunk asinine pep rally advice like “ignore your competition!”

the authors of those books shared previously are professors, meaning they don’t know anything about running a business. an academic merely defines ideas, he cannot use them in a sentence.

ground rules

this post is not about local business. starting a sandwich shop, when there are 1,000s of sandwich shops, is not the same thing as starting a software company that anyone, anywhere, can access instantly.

only for-profit business strategy is relevant to this discussion. if your company does not exist to make money, call it a non-profit or read something else.

you are encouraged to disagree with evidence-based reasoning in the comments section below, and i will guarantee a thoughtful reply.

underscoring all of this advice is honest and ethical behavior.

maxims

let’s begin with the bottom line.

- there are two kinds of entrepreneurs

- competition inspires moral relativism

- we rarely achieve what the business plan says

- conventional advice is garbage

click an argument to specify your interest, or read along below.

two kinds of entrepreneurs

you can be an innovator or an opportunist.

in middle school, high school, and college i was the latter:

- sold candy (arbitrage)

- taught guitar (sold dreams)

- catered hookah, made promotional products (services)

did i eat my own candy? no. have i ever taken a single guitar lesson in my life? no. do i smoke hookah? absolutely not.

in each of these scenarios i identified an opportunity to “fill a gap in the market” and make a few bucks, so i took it. in none of these scenarios was i an innovator.

after college graduation and a couple full-time jobs, i transitioned to innovation. i began thinking about new ideas that hadn’t been tested in the market. i wanted to challenge myself creatively and i wanted to be first.

was vanity involved? maybe. but there are measurable benefits to being first to market, too. authors Ries and Trout stress in 22 Immutable Laws of Marketing:

it is better to be first than it is to be better.

disagree? consider these market leaders:

- Coca Cola, first soda beverage

- Charles Lindbergh (1st to fly solo across the Atlantic, who was 2nd?)

- Hertz, first in rental cars

- Heineken, first imported beer

- Playboy, before Penthouse

- Time, before Newsweek

- Band-Aid, Jello, Q-tips, Velcro…

it is impossible, therefore, to be first and also an opportunist. we must decide before writing code or raising money, if we even want to have competitors at all.

Peter Thiel’s approach in Zero to One offers this summary:

“It is easy to do what we know, adding more of something familiar, going from 1 to n. But every time we create something new, we go from 0 to 1…”

Thiel posits that competition is for losers. to really win, build a monopoly.

why, then, are there so many competitors to so many great products?

competition inspires moral relativism

in Mere Christianity C.S. Lewis argues we don’t commit acts of malevolence for malevolence sake; we do it for our own benefit. his implication? it’s often easier to do the wrong thing than the right thing.

why else would someone rob a bank and risk being shot, when they could work 25 years instead?

suppose you build a tool that helps colleges manage buyback programs at their book stores. with a static cohort of ~4,000 universities in the US, a “fixed pie” approach to revenue forecasting is not unreasonable.

unfortunately, more markets are a fixed pie than most technologists (and their investors) care to admit.

in categories where new entrepreneurs enter a market daily, there are other entrepreneurs dropping out. it may be the case, then, that some target audiences are better defined as revolving than growing.

and even for those truly growing markets, namely ecommerce, more vendors competing means a lower quality product for end users. do we think Google’s search algorithm would be as competent if there were 100 Googles? i don’t.

(this realization bears no correlation with my feelings toward Google, it’s simply the reality of their monopoly: a superior product i can’t stop using because Duck Duck Go and Bing still suck.)

back to morality.

psychologists have heavily documented the concept of Moral Flexibility in the context of religion and personal character. can this relate to competition?

consider this: humans can rationalize any behavior, even contemptible ones, as a survival mechanism. as an “able to sleep at night” mechanism. and because we prefer to remain consistent with our positive perception of ourselves, or the positive perceptions others have toward us, the rationalization is circular.

in business this means we are especially talented at demonizing our adversaries, because if a competitor is “evil” they can be justly stricken down by the hands of God or Karma. (humans are also inclined to narcissism)

what better ingredient to encourage this demonization than increased risk?

the risk of a fixed pie, a shrinking addressable market, the fear of incoming opportunists who notice a “gap in the market” not yet filled by the innovators.

each of these risks stands to fracture our moral compass.

we rarely achieve what the business plan says

how many times have we been promised a better ______, only to be let down?

there’s no better microcosm of this treadmill than Kickstarter. Kickstarter is where superior ideas get slaughtered by inferior execution.

off the top of my head, through Kickstarter i’ve attempted to improve my:

- wallet

- corded headphones

- entertainment options

- diet

- art consumption

like the popular tourism souvenir of the 90’s, i deserve one that reads “i pledged $1,000+ on Kickstarter, and all i got was this stupid t-shirt.”

most entrants to established markets are like Kickstarter campaigns, minus the t-shirt and sticker rewards. they are delivered by opportunists with exceptional pitching, but not innovating, ability.

Ello was supposed to conquer Facebook as the first ad-free, we-don’t-sell-your-data social network. now it’s a circle jerk for visual artists… aka people who have no money and will never pay for anything, especially not a social network.

Shyp was supposed to wipe out the USPS, but didn’t realize UPS and FedEx and DHL already did that. so after hand-packing $62.1mm worth of subsidized goods (including my guitar, twice, and my Xbox, 3 times), they shut down.

when a dozen Fomo competitors entered the Shopify App Store in mid 2016, our first reaction was nervousness. will they clone our features, build new ones, and will our customers notice?

what actually happened was they built 1/10 of our features, didn’t develop anything new, and charged less. existing clients didn’t switch, but potential clients didn’t always find us first, either.

when competing technology platforms are launched by zero-conviction opportunists, their Day 0 business plan to build a better mousetrap usually results in a Day 365 cheap, shitty clone.

great entrepreneurs (innovators) don’t wake up to build cheap, shitty products.

where this inneficient competitive landscape leaves us:

- the best products suffer (better product != more exposure)

- the worst products have mediocre success

- 99% of the world’s problems are unsolved

- customers powering mediocre copycats are unaware a better solution exists

- rinse, repeat

conventional advice is garbage

i chuckle at startup maxims like “ignore your competition” or conversely, “clone them and charge less.”

as Seth Godin reminds us, if you race to the bottom you just might win.

investor Sarah Tavel once riffed bearish faith in companies like Instacart (grocery delivery), noting the world’s best disruptors (ie Uber) are both better and cheaper.

grocery delivery in 10 minutes is great, but not everyone can afford to pay extra for convenience. on the other hand, Uber is cheaper and better than a Taxi cab, so the decision is a no brainer.

conventional advice is also dangerous because it’s based on data, and the problem with data is it can be interpreted to confirm any narrative. while this interpretation risk obviously applies to subjective ideas as well, data-driven subjectivity is especially harmful because contrarians (free thinkers) are more likely to be ostracized for questioning it.

(observe here a Nobel laureate attempt to debunk Global Warming; later he was pressured to resign from the American Physical Society, whose peer members remarked that the evidence for global warming is incontrovertible. is it? data cuts both ways.)

a less political example: in the late 1970’s the Pepsi Challenge took off. ordinary consumers were asked to sip a bit of Pepsi and bit of Coke, in unmarked containers, then vote on their favorite. Pepsi was the chosen beverage most of the time, and this “data” was used to declare them the winner.

fast forward a few decades, Malcolm Gladwell’s own assessment in Blink took another approach: people enjoyed just a sip* of Pepsi more than Coke, because Pepsi is sweeter. but if you test subjects with a full can, they choose Coke.

in what scenario is a soda drinker likely to consume just a sip of something? never.

the Pepsi Challenge had a fundamental flaw, yet the data drove the narrative that Pepsi is better, when in reality they’re a me-too clone, overpaying for the likes of Michael Jackson to compete with Coke’s much larger brand: America.

translated to technology, instead of a 2 ounce sip vs a 12 ounce can, consider time our mutable variable. on launch day, Ello looked like a strong contender to Facebook. a couple years later, it looks like a joke.

in dichotomous poetry, first-to-market products often look like a joke in the beginning*, then look obvious later on. my favorite example of this is Robin Hood, the world’s first zero-fee stock trading platform. five years after being rejected by 75 investors, they’re now valued at $5.6 billion.

suffice to say: conventional advice doesn’t encourage unique perspectives. we also give too much credit to existing perspectives in new clothes.

take the e-reader. the point of view, the conviction, is that we don’t need to thumb through physical pages with a pen to read a book or take notes. a step further, we don’t even need color. after all, most books are black and white, right? then Audible had another idea, that we don’t even need to read at all.

every competing player in the publishing space shares 1 of these 2 points of view, yet pretends to differentiate on features or pricing.

but consumers prefer not to juggle too many paradigms, and usually we pledge allegiance to whichever company was “first” to claim a point of view with which we most resonate.

Geoffrey Moore’s Crossing the Chasm steps us through this psychological arch in almost painful detail, demonstrating example after example to illustrate we:

- root for the underdog,

- back it [with our resources] to ensure its leadership position,

- in order to prove ourselves the real victor,

- that we “chose the right one.”

again, the Consistency Principle at work. and even more evidence that conventional wisdom for handling your competition or startup strategy is trash.

summary

America is the greatest country in the world. i’m thrilled citizens have the opportunity and freedom to compete with one another, even when they don’t have anything new to offer.

this is because free markets work both ways… incumbents ought to be punished or prosper, pending their ability to meet ever-changing customer demands.

but this acknowledgement is not mutually exclusive to my disgust for me-too competitors.

it simply doesn’t make sense to humor 1000s of gas and electric companies with their own “pipes,” thus the government regulates it, a controlled monopoly.

it doesn’t make sense to stockpile 1000s of screwdrivers, so manufacturers have conformed to mostly Flat-head or Phillips.

as more entrepreneurs agree, the more problems we’ll solve, and the larger our pie will become.